Why Inquiry?

There are a hundred reasons why inquiry-based learning is a great choice, but I’ve focused on two specific reasons why I wanted to use it for my grade nine students:

First, my students have spent the last 10 years learning skills, seeking information, and developing interests with a variety of teachers from various backgrounds. More than that, they’ve spent 15 years developing their own personal interests and skills both in school and outside of it. Why not use those skills? They can pull from every domain they’ve ever encountered, and can combine those skills to create their own learning system.

Second, when you give students autonomy, freedom, and permission to explore their own interests, set their own goals, and determine their own direction — while having access to the largest exploration space possible (thanks, Internet!) — you have the opportunity to supercharge students’ motivation and engage them in a way that other tasks or activities can’t.

Problems in the real world — or even in school — are rarely solved by using one skill or by pulling from a single domain. Inquiry-based learning lets students practice developing their own strategies, reflecting on each of their decisions, and exploring their own interests. When we share that with our classmates, teachers, and audience, we create positive associations with that process and can develop life-long learning strategies we can adapt and use in any situation.

The Inquiry Cycle:

Inquiry can have anywhere from three to eleven steps. I decided to keep things simple and casual. The key here was that the students:

- could determine their area of focus;

- felt supported and confident in their exploration, and;

- had time to reflect on their choices and progress at several points during their inquiry.

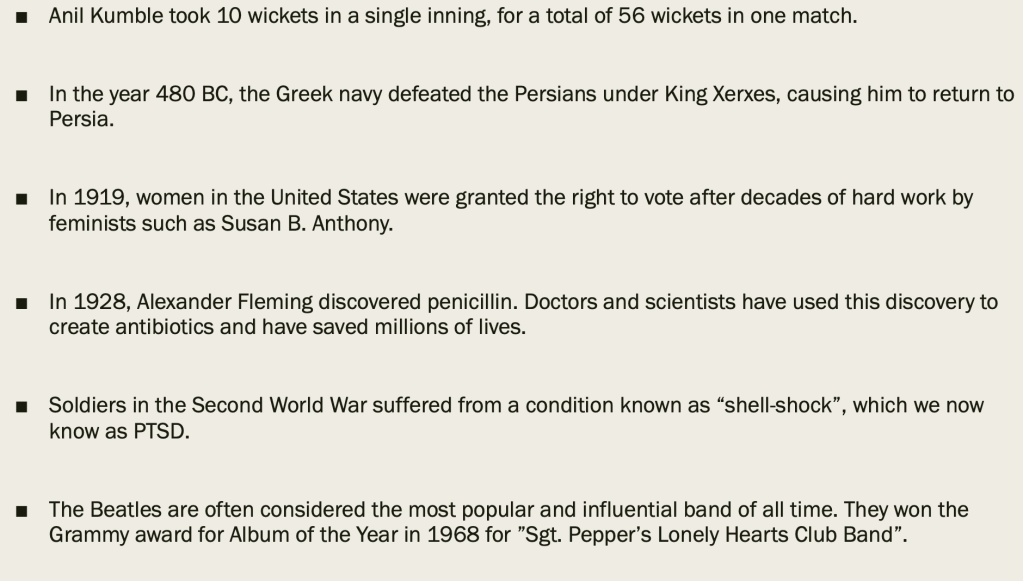

1. Prompt

To start the process, I provided my students with a “prompt”: A selection of topics my students (probably) knew nothing about. Choose one, find out what you can, then tell me about it. The difference in engagement was immediate, and even students who were not particularly interested in their chosen topic were able to find and share information, facts, and stories they were interested in.

2. Reflect…

After one or two classes of individual research, students had a low pressure chat with their classmates about what they’d learned so far. I was hopeful that they would also share their fears and uncertainty about the process, and become more comfortable not quite knowing where we were heading.

Next step was the “teacher” chat. I consider myself quite approachable, but students were… reluctant to meet with me and tell me what they knew and what they found interesting. I also had to be careful not to push them in a direction I found interesting, and to simply support what they’d done so far, and gently suggest further areas of exploration. I did this by listening, then asking simple questions, and finally suggesting large, general areas of inquiry for the next work period.

I’ll admit my success in guiding them was mixed: Student reaction to my suggestions ranged from “Oh that’s interesting…” to “Do I have to research THAT?” to “Pass.” However, they seemed eager to get back to researching (or at least using their iPads…), and every student seemed genuinely knowledgeable about their topic.

…and Refine

This was the hardest to define, and the part where it was most tempting to “lead by example”. But demonstrating your own topic and refining it as an example gives the students a specific idea of their success criteria. That’s fatal to the inquiry process. I explained what ore refining was (Not. Helpful.) and then explained that they now knew more about their topics than I did. How would they describe their topic? In my chats with students a few said “The topic says ____, so I guess I can’t talk about ____.” My response was always “Did I say that? If you’re interested, research that instead.” Their refined topic did not have to have anything to do with their original topic, but it “should” be the result of their research, which grew from that initial topic.

Students refined their topic after their chat with me, and most of them eliminated the specificity of the topic. For example, “Soldiers in the Second World War suffered from a condition known as ‘shell-shock’, which we now know as PTSD.” became simply “PTSD”. I had concerns that this meant my students were not finding specific avenues and details in their research, but also pleased that they understood they had autonomy and freedom from the original topic.

3. Goal-setting and focused exploration

Look… I’ll admit I cheated a little bit. I asked my students when they felt they would be ready to share their work or “final product” (not final, not a product) and they — being teenagers — chose the last possible day before we started final test review. So I suggested that too LITTLE time (tomorrow) was bad, but so was too MUCH time (Friday before the test). They might lose focus! So “they” (sorry, guys) decided on Wednesday and Thursday to share their projects. I also asked them if they knew what form their final product would take, and they all chose powerpoint presentation.

(Note: A few students expressed regret in choosing a powerpoint presentation, and wished they had done something more adventurous. Two things: First, you’re not dead! Lots of chances to be adventurous next time. Second: There’s a reason powerpoint presentations are so popular. You get to be creative, but there’s a built-in structure. It’s a great way to share!)

On Monday and Tuesday I confirmed that my students were ready to share, determined the order to present randomly, and students sent me their powerpoints before Wednesday/Thursday’s class.

4. Share…

One student was absent and presented at a later time, and one had not attended as many classes and sent a video of her presentation later that week, but the rest of the students presented their powerpoints on Wednesday and Thursday. Each student brought their own perspective to the original topics, and each powerpoint made great use of text and images. The powerpoint files are shared below, click here to skip to the next section.

…and celebrate

An underrated part of the inquiry process is the necessity for celebration. Regardless of students’ feelings about their final product, it’s important that students acknowledge their progress and hard work. This allows students to connect a positive, communal experience (sharing candy and watching a movie!) to the difficult process of self-regulated learning and reflection.

5. Reflect

I then gave students a short self-assessment and reflection. I was so surprised and pleased with the students responses, and no student simply filled out “5/5” “Wouldn’t change a thing.” or “Boring.” They all provided me with thoughtful, insightful responses.

Rather than a grade, I chose to give specific, positive feedback that directly addressed students’ reflections. “In your reflection you said…”, “I noticed that you wish you had…”, or “Have you considered…” Because I gave the students no expectations or requirements, it’s important that the students’ view of their own project was the most important part of their feedback. Of course I included (true!) compliments and expressed how proud I was of the work they’d done.

My final reflections:

I’d be remiss if I didn’t address the elephant in the room: How is this different from any normal research project where my students go home, search online, and present their work?

Three ways:

- Meta-cognition: Students are made aware of the process, reflect on their progress, and start to build conscious self-efficacy and explicit understanding of their own motivation and work habits.

- Student-driven: Rather than a rubric or specific instructions, my students were expected to set their own goals and determine their own expected and ideal outcome. The focus is on what satisfies their internal requirements, not mine.

- A cycle: Students come away from inquiry-based projects understanding that the work is not done. What comes next? What have I learned? What worked, what didn’t, and why was that the case? Unlike many other assignments, I genuinely believe some of my students will continue looking into their topic for their own education and interest.

Overall, I was incredibly pleased with the students’ work and presentations. I was also very surprised by how self-aware my students were in their reflections. They all saw areas for change or improvement, and understood where they could go next. We all came away from the experience with generally positive feelings, and as I learn more about inquiry-based learning and refine my own process, I look forward to using it again with more classes in the future.

Back to 1. Explore

So what about me? What do I do next?

First… Celebrate! I did it! I designed and implemented a student-driven research project in my class.

Then… Create this webpage to share my and my students’ work with coworkers, friends, and other students. (Done!)

Finally… Reflect and begin again. What worked and what didn’t? I’m teaching Grade 8 right now, Grade 7 and 9 next year, how can I lay the groundwork for a project like this in earlier grades? Is there another version of this project I can use with younger students?

Being a teacher is really one big inquiry project, so the cycle begins again. Thanks for reading, I hope you found it interesting!